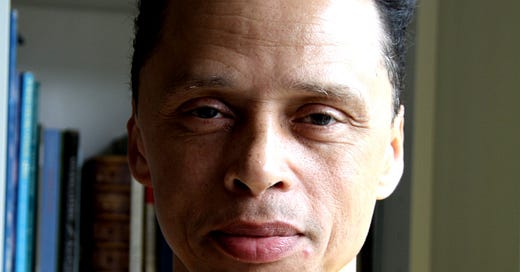

Ashleigh Nugent: “I know what white British men are thinking because I am them”

The author on living on the threshold, foisted identities and visceral feelings of otherness

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week I’m speaking to author Ashleigh Nugent, who is of Jamaican and Scottish heritage. Ashleigh’s debut novel, Locks, follows Aeon, a “mixed-up and mixed-race teenager from a leafy Liverpool suburb, desperate to understand the Black identity thrust upon him.” Aeon heads to Jamaica to immerse himself in Black culture, but things take a turn when he finds himself as the ‘white boy’ in prison. Based on Ashleigh’s own experiences, Locks is a gripping read, and I was excited to hear the story in his own words. Read it below.

How do you define your identity?

The words I’ve used have changed over time. I was born in 1976, when it used to be polite to call people like me ‘coloured,’ then ‘half-caste.’ Nowadays, I just call myself mixed-race, but of course race doesn’t exist. As a scientific category, it’s a fallacy, yet it exists because we’ve made it.

My dad is Black Jamaican and my mum is white Scottish, born in Yorkshire. I was brought up on the outskirts of Liverpool. I always describe myself as peripheral, marginal and liminal – I was brought up in a white leafy suburban village. I wasn’t really a Scouser, I wasn’t really in the inner city. Scousers never really accepted me as being fully theirs, and I was never accepted as being Jamaican or Black even though I was Black to the white people where I grew up.

Not only are people like us between two worlds, we can see both worlds. I know what white British men are thinking because I am them, I was brought up with them. I watched the same TV shows, sat in the same classroom, made the same racist, homophobic and sexist jokes. But they don’t know me, they can’t know what I’m thinking and feeling because they don’t know my experience of having melanin.

Liminal also means on the threshold, and as mixed people we’re born in a perfect position to take this whole culture forward and write new stories.

In Locks, the story follows mixed-race Aeon as he travels to Jamaica to connect with his heritage. But when he gets there, he’s perhaps not seen in the way he wants to be. Is that an experience you shared?

It was a shocker [going to Jamaica]. I understood the culture, but going there I found myself stabbed and in prison, beaten unconscious while they shouted “F up the white man.” You can’t get any more visceral a feeling of your otherness in a place you expected to feel belonging.

What was your connection like to your Jamaican heritage before that?

I didn't really have any connection to my Jamaican roots. My dad came over in his early 20s and did very well for himself in the NHS, where my mum was a matron. They got to the top of their careers and in order to do that, they had to get their heads down and ignore the abuse they got. They never told me until I was much older how difficult it was – there were rumours going around the hospital that my mum was a prostitute and that’s why she was with a Black man, or because she was scarred from a fire.

We never had a conversation about me being Black or mixed either. The only conversations I did have were when people started pointing things out or called me coloured. I would stand on an upturned bin looking in the bathroom mirror trying to find the stripes of colour. I know it sounds strange now, but as a child I didn’t understand that my dad being a 6’2” Black guy with a big afro looked any different to my friend’s dads.

My mum would sometimes eat haggis and sing Flower of Scotland and we had the Jamaican coat of arms on the wall, but we didn’t discuss it at length. I got interested in both aspects of my heritage when I started studying for myself.

Has your sense of self shifted over time? In Locks, Aeon builds his idea of Blackness through clothes and music, but soon discovers it’s deeper than that.

My relationship with my Blackness has shifted massively over the course of my life and it’s still shifting now. I’m doing a lot more work with people from Liverpool 8, Toxteth, and the Black community. I’ve hung around them since I was 14, but I’ve never lived there.

Only now am I starting to accept that I’m accepted by them. I never thought they’d see me as being one of them because I didn’t understand the things that they’d grown up around, like sound system culture or rastas, people who were into Black Power movements or marching in London. I never knew anything about this stuff until I was an adult. I knew about as much as white people in the suburbs because I was a culturally white guy.

I decided to start acting upon this identity that was foisted upon me by white society, which was this Black lad with a chip on my shoulder. I had to look to America for Black male role models, and I wasn’t looking to Cornel West or W.E.B. Du Bois. I was looking for people I could access on the Tim Westwood show – let’s not go there with him… But it was Tupac, De La Soul and Bob Marley, and seeing how they expressed themselves and their identity in music so vociferously.

I felt like I couldn’t live up to that because I was just a spoiled kid from the suburbs, with lovely clothes and loads of pocket money. Yes I’ve had my head kicked in while people shouted “you Black bastard” or ‘n*gger’ and ‘c**n’ at me, and I’ve been harassed by the police since I was 14 and locked up in cells. But it didn’t feel like anything compared to Compton or Kingston, which I really felt related to being a Black person.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

I can’t see any negatives. Locks is the beginning of the unburdening. Race was a burden, but now I’ve chosen to see my identity as a very positive thing. It’s made me who I am now.

You are in control of your own thoughts and feelings, so you can get curious about things and treat them with humour and lightness. There is some hardcore stuff happening here, but let’s smile, laugh and enjoy our lives.

Can you sum up your mixed identity in one word?

Beautiful. It’s really, really beautiful. There’s so much brutality to the history that has made me, yet we’re having this conversation. We get to use all of that to tell stories that are hopefully the beginning of the unburdening for so many people.

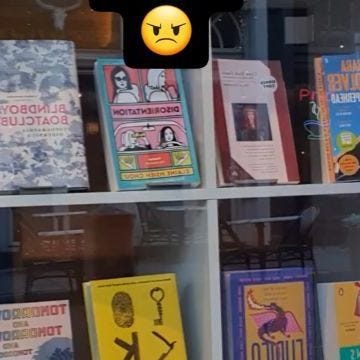

Buy Locks on Amazon, Bookshop or anywhere you get your books. Next week I’ll be speaking to author and journalist Lucy Fulford. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday.

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

Great piece :)

Loved this piece! I related to so much of it! The feeling of knowing how to “be white” because that’s what you’re surrounded with and raised with, yet all those white people will never know how it feels to be Black.

And the fact that the author’s parents never discussed race - my upbringing was the same.

It is heartening reading these stories and knowing that my experiences and feelings aren’t isolated. These are important pieces!