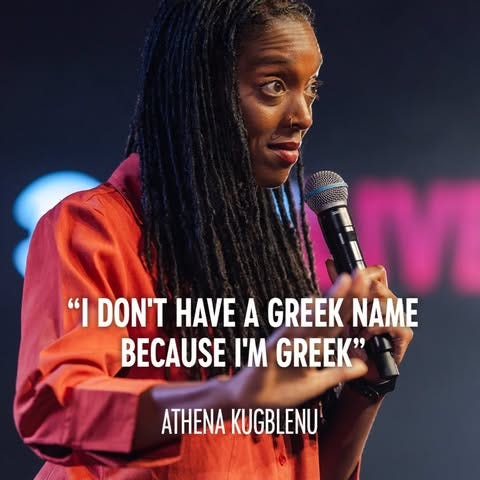

Athena Kugblenu: “I always understood I wasn't where I came from”

The comedian and author on the importance of culture, standing on the same side of the line and doing the work

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week’s guest is comedian and writer Athena Kugblenu, who is of mixed-Ghanaian, Guyanese and Indian heritage. Most people don’t think Athena looks like a ‘typical’ mixed-race Black person, which is exactly the reason I wanted to speak to her. There is no single way to look, feel or be mixed, and Athena’s conversation will definitely make you think twice about identity. Read her story below.

How do you define your identity?

My dad is Black African from Ghana. My mum is from Guyana, she’s Caribbean-Indian. I personally describe myself as Black mixed-race as a shorthand. That can confuse people – people’s perceptions of what mixed-race means in a Black person is somebody who is half-Black, half-white. It’s important to tell people I’m mixed-race because it’s true – people’s reactions to that can be quite telling.

What presumptions do you think people have made about you?

There are people who are familiar with what a half-Black African and half-Asian person looks like, paticularly if they’re from the Caribbean because that’s a lot more common there. The idea that the Caribbean is Black is a huge misconception. I think I've got a very typical look for someone who is half-Indian, half Black-African.

You mentioned that people don’t want you to be complicated, but we’re all so multifaceted. Our identities are affected by so much more than our skin colour.

Sometimes the pursuit of trying to find a mixed-race narrative is not helpful because it’s impossible. What you want to do is eliminate the idea that there is a story. There’s such unique ways to be mixed-race. It’s not just about where your parents come from, it's how you were brought up as well.

My mum wasn’t particularly connected to her Indian side. We watched Indian movies and kabaddi, cuisine-wise we ate Indian and Caribbean-Indian food. My family has Gujarati heritage, but I don’t speak the language and I’ve never been to India, or even back to Guyana. That means I’m very different from someone who is half-Indian but had Indian culture in their household.

My dad never taught my brother and I the language from Ghana either. He wasn't really around that much, so even though we felt Ghanaian, we felt very differently to someone who has a parent that’s present and teaches them their culture. I would prefer a world in which mixed-race wasn’t even a label because you’d need about 10,000 to adequately cover off everybody’s experience.

Has your identity ever been a question for you, pr have you always felt confident in yourself?

I’ve always, without doubt, felt Ghanaian, Indian and Guyanese. There are some factors involved in that – I don’t have a white family, and it's a lot easier when your whole family is brown. I say that facetiously, but also quite seriously, because if there’s a line of white supremacy, you will all occupy the other side of the line. You don’t have that conflict you can have when you have white family.

I’m very much a diasporic child. We ate Indian, Ghanaian and Caribbean food, we always had a house full of uncles and aunties, I always understood I wasn't where I came from. I never felt that me being brought up in the UK negates where I come from. Being aware of my parents’ story and what it meant to be a second generation immigrant, I was never insecure about my cultural identities.

In primary school, I was one of three Black children in my year, including my twin brother. I never had a sense that I was different, or that my difference was a problem. Secondary school was more diverse, and when you ate something different at someone’s house, you didn’t care. You just knew that people were different. It's not that you shouldn't feel different, it's that your differences shouldn't bother you.

Do you think that being mixed has impacted your perspective on life?

My mum’s Indian side of the family were, and some individuals probably still are, incredibly prejudiced against Black Africans. Racism on both sides is a big part of the Guyanese story. Whilst things have changed now, there was a real venom between Black and Asian people that made my mum's marriage very challenging for our family to accept.

One of the ways people don't realise white privilege works is that it pretends that only white people are capable of racism. I come from a world where white people weren't in the equation, so I immediately was able to decenter white people very quickly, which was very beneficial to my understanding of the way race works. I’m able to see things in a more holistic way. That’s a privilege – I probably wouldn’t have that attitude if I was Black on both sides or had a white parent.

It’s also been helpful in the kitchen having Indian and African parents. There's no denying that those cuisines and cultures belong to me, and I can occupy those spaces with a decent amount of integrity.

I do think being mixed-race and being comfortable with it, having parents who know where they come from and who were able to tell you that, in their own ways, is healthy, but you have to get there. I didn’t always think this way.

Did you ever speak to your family about being mixed?

We never spoke about it growing up. My twin brother and I started to speak about it more once we had children – we actually had children on the same day. His partner is white English, my partner is Black Nigerian. My brother has children who are mixed, but in order for them to identify as Black he kind of had to invest in the one drop rule, which is quite heinous.

What happens with Black people in general is that we’re consumed with the idea that our kids will be Black, so we don’t have to think about it. Now you’ve got this child who is further removed from their heritages, so you have to do the work for them.

If you’re a mixed-race person in the diaspora, you get to a point where if your parents haven't given you really firm things for you to hang your identity on, whether that’s language, cuisine, dress, music, film, whatever, your kids won’t have that. It's not even about what you teach your kids, it’s about what you teach yourself because they can’t know what you don’t know. We have third and now fourth generation children coming out, so we have to accept that our kids are British.

I do think our parents should take responsibility for trying to Westernise us and give us English names. It's a very common story for West African parents to purposely not teach their kids the language because it felt like it could be a negative thing. No one believed in the narrative of being British subjects more than older generation Caribbeans and West African people. That has left us, particularly as second generation Black people, with a vacuum. That vacuum is just going to get bigger because we don’t have a tangible and real connection to where we come from.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

The holiday destinations, a potential passport. If you get it, that open-mindedness and ability you have to decode society comes a lot easier to you.

Can you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

No. That’s my word. We’re still talking and we started over an hour ago, so I could not.

Next week, I’ll be speaking to author Sharada Keats. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Shop Mixed Messages tote bags and bookmarks on Etsy now.

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

“It's not that you shouldn't feel different, it's that your differences shouldn't bother you.” 👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽