Aube Rey Lescure: “My places of comfort are where I walk down the street and no one looks twice”

The author on the building blocks of her Chinese identity, cultural perceptions of masculinity and the push and pull of being mixed

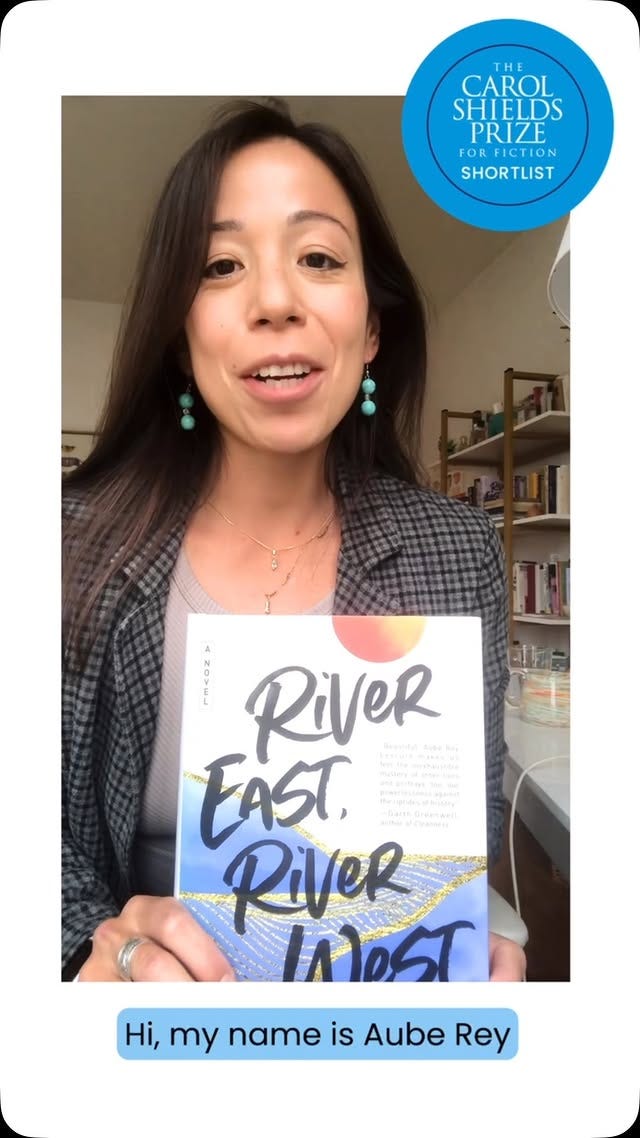

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week’s guest is author Aube Rey Lescure, who is of mixed-Chinese and French heritage. Aube’s debut novel, River East, River West, was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2024, and follows Alva, a fourteen-year-old teenager feeling betrayed by her American mother’s engagement to their rich landlord Lu Fang. Plotting her escape, she transfers to an exclusive American School, but it’s not everything she imagined it to be. It’s an affecting read, and I’m excited for you to read Aube’s story below.

How do you describe your identity?

I grew up with Chinese and French as my native languages, and those are the terms I’d been taught by my parents. In my English-speaking life, I don’t really say I’m mixed. I just say I’m half-French, half-Chinese.

My mother would use the word métis in French. In Chinese, it’s a similar word, hùnxuè'ér, which translates to mixed-blood child. Growing up, it never crossed my mind that they would be pejorative. I don't think they really were in the context and societal era that I was using them in.

Later in life, I learned that the descendants of American soldiers in Korea, Vietnam and Japan faced a lot of discrimination if they were hùnxuè'ér. By the time I was growing up in the ‘90s and 2000s, being a hùnxuè'ér in China came with positive stereotypes almost, which also came from this idea of whiteness being desirable.

Your mother is French, which is perhaps not what people expect. Did that affect how people saw your father?

I think he was seen as having achieved something by marrying a white woman and having a child with her. In China, taxi drivers love quizzing their passengers on their ethnic makeup if you look like you’re a bit Chinese. They’d always ask if I was foreign or where I was from, assuming that my mom was Chinese. When I said my mum was French, they’d say ‘wow, your dad did well.’

When that’s reversed, there’s more of a societal stigma, an idea that the woman married the man for money or for status, or more insidiously that an Asian woman is betraying her race by being with a white man. It has a lot to do with cultural perceptions of masculinity, the idea that a man from that culture being with a white woman was ennobling, but that women were selling something of themselves.

You’ve lived across continents, in Asia, Europe and the US. How did your sense of self change in these spaces?

It's definitely shifted a lot over time. Your physique changes from childhood into adulthood, and physically the way you pass, or don't pass, or scan for other people. A lot of my sense of self is based more on how other people perceive me than how I feel within myself.

When I was a kid, I looked a lot more Chinese. Walking down the street, I wouldn't necessarily get stares of ‘oh, she's foreign.’ Now, I’m aware of those stares. At the same time, I’m foreign to French people. My places of greatest comfort are places where I can just walk down the street and no one looks twice.

I struggle with this constant mental voice that says I’m not ‘you're not really a Chinese person and you're not really a French person.’ If someone told me I wasn’t French, I’d be horribly offended, but I do feel like an outsider. If someone tells me I’m not really Chinese, part of me thinks they’re right. It's exhausting to feel that way, because if you self reject that identity, you end up belonging to nothing. In recent years, instead of thinking I'm half of something, I would like to try to say I’m French and Chinese. The word half is true in a genetic sense, but the idea of having a fractional basis of identity engenders this internal sense of never fully being in one culture or another.

What was your cultural upbringing like, having grown up around the globe?

I was recently in Hong Kong, and I bought a modern spin on a traditional qiaopao for an event. I loved it, but it crossed my mind, ‘is this cultural appropriation?’ Part of me was like, ‘hell no, I can wear this dress, I am Chinese,’ but it was striking that I considered that. Chinese is my native tongue. I spent the first 16 years of my life growing up there. I was very close with my Chinese family and I kept repeating to myself that there's so many things in my childhood that make me very Chinese. It feels bad arguing with yourself about the credentials to claim.

But I also have a foreign passport, which allows me to go places a Chinese passport wouldn’t. I have a French mum, and I was considered a foreigner when I walked down the street in China. It would also be a lie to say that I was living in China as a Chinese kid.

How much of Alva’s story in River East, River West was true to you?

My main character stayed so close to my own identity because it's what I knew how to write, but when she speaks about not being “the right kind of mixed,” not getting the ‘best’ combination of features, I hope it was obvious that we are inhabiting the mind of a teenage girl.

This also represents her wish to both belong and also stand out. There’s this tension when a lady on her new school bus calls after her, telling her, ‘your Chinese is so good.’ Her being seen as foreign and not Chinese anymore, you contrast that to that opening scene in the book where she's sitting there thinking ‘I don't look white enough,’ and that speaks to the push and pull in my own personal upbringing, although I didn't necessarily wish I looked whiter as a kid, I had a white mum next to me all the time like a lighthouse.

I am so grateful for being in a Chinese school system and world until I was 14, for all the good and the bad. My mother did it for me to feel connected to my culture and heritage, and it shaped my character. Honestly, I wouldn't change a thing. It cemented something. When I go back to China and people say I’m foreign, I go back to those first years of my life, the building blocks of my Chinese identity.

What's the best thing about being mixed for you?

There's so many great things. Having access to two maternal languages and cultures that are so very different, having Chinese coexist in my head along with French. The curse of feeling like a perpetual outsider builds some muscle in being OK with being a loose atom. I do feel very at home in the world when I'm travelling, because there's nothing so dramatically new for me. Everywhere can kind of feel like a place of temporary home and shelter.

How would you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

Feeling like you're standing at the periphery of a group, wanting to be recognised or belong, but always facing some resistance… Is there a word for that? It’s elastic, in many different ways. It's like trying to push into one place, or moving back if you need to act a different way.

Get your copy of River East, River West here now. Next week, I’ll be speaking to A Wilder Way author Poppy Okotcha. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Shop Mixed Messages tote bags and bookmarks on Etsy now!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.