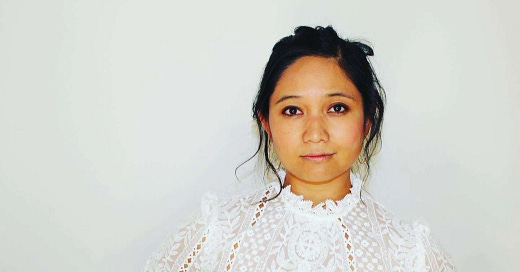

Dani Heywood-Lonsdale: “Growing up, there wasn't an urge or necessity to define ourselves”

The author on questions from strangers, her Filipino comfort foods and the hidden truths she’s bringing to the surface

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week’s guest is author Dani Heywood-Lonsdale, who is of mixed-Hawaiian and Filipino heritage, but of course there’s more to the story than that. Dani’s paternal roots lie on the island of Moloka’i, which she refers to as the Sandwich Islands throughout The Portrait Artist, her debut novel. The story is set between London and Oxford, where a mysterious painting sparks rumours amongst 1890s society. It’s a twisting tale on race, fame and long-kept secrets, and I was thrilled to speak to Dani about her own story – read it below.

What’s your racial background?

My dad was born and raised in Hawaii, on Moloka’i, one of the smaller islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. He’s also Spanish, Portuguese and a bit Chinese. My grandparents were in Hawaii working in the pineapple fields.

My mum was from the Philippines, but her grandparents, or at least one of them, was from Spain. Two island people meet, of all places, in freezing cold Minnesota. I was born and raised on the West Coast. I grew up with these two Island cultures at the core of the household, yet had a very American experience. I've been in England about 14 years now and I've never felt more at home.

What was that cultural upbringing like?

Outside the house, it was very much about fitting in. Within the house, it was definitely food and travel. My mum is a wonderful cook, so I was lucky to grow up with a lot of Filipino dishes, like lumpia. When I’m ill, the comfort food I want is sinigang. My mum is such a feeder and provider, so it was always my house my friends would go to after school.

In terms of travel, we’d go to Hawaii every summer where most of my dad’s family was. I grew up playing with my cousins in my grandmother's house. I have memories of my grandparents picking beans and tilling the soil while we ran around barefoot in the garden. I have all of these really vivid images of Hawaii, but because we went there every year, we never travelled to Europe or anything. I was reading stories and fairy tales that took place in the English countryside, or the hills and forests of Germany or Switzerland, so I think there was always a hunger to explore those places.

How have you held onto your culture now that you are in England?

Every now and then, I'll have a craving for something, and my husband and I will go and stock up on coconut milk or some of the vegetables you can't get in a typical supermarket here. He’s the cook, my mum taught him some of the recipes. My parents do come to visit us quite often, so my mum will make batches of food for the freezer. My children love it.

Another way that we try to preserve it has been traveling. I think it’s incredibly important for my children to grow up knowing there are many ways to live in the world, especially because we live in the Cotswolds and it's predominantly white. Two years ago, we made the trip to Singapore and the Philippines and my mum showed the kids her family, what they eat, how they’d go to the beach… It's quite nice to be able to carry on those things in a subtle way, but also embrace and appreciate growing up here, because I do think there's a reason I feel at home in England too.

Why do you think that is?

I think much of it is tied to the literature that I loved reading growing up. The scenes here are so familiar, the countryside or Victorian cityscapes. I also really like the British sense of humor. I like the self deprecation of it, which combats the sometimes overwhelming American optimism.

You feel very settled in your sense of identity – has that always been the case?

I've always been secure. My parents have always been very present and supportive. I wasn’t completely reflective on the mixed-race aspects of my identity until I was older, because growing up I was surrounded by diversity. It’s only when I left that I became more aware of how I was different from other people.

Did you ever speak to your family about being mixed?

Not really. There wasn't an urge or a necessity to define ourselves. Writing this book in cafes, strangers will ask what I’m working on, followed by “where are you from?” If I answer “I live in Oxford” or “I was raised on the West Coast,” it never stops there. They always want the next question, which is “where are your parents from?”

When I say “my dad's from Hawaii, my mum's from the Philippines,” it sparks another conversation. So I've had more of those conversations around identity and what that means with complete strangers, but in a really lovely way. I've never felt I was judged, it was more curiosity.

Your book, The Portrait Artist, explores race throughout history – what came first, your research into this area or the story?

The characters in my story are all completely fiction. I think they had to be fiction, because there's no record of people like them that I could find. My book is about hidden truths, and I knew the particular story I wanted to explore and why this person had to stay hidden.

Even though race becomes a defining factor later on in the story, if you were to reread it, it's really quietly interlaced throughout, showing how we’ve always been here.

Without those records, how did you conduct your research?

I was filling in the gaps, so I found lists of neighbourhoods where certain races predominantly were, lists deciding somewhere was predominantly Chinese because there were a lot of opium dens, for example. So you have to dig a bit.

I also looked for depictions of anyone non-white in art. A few paintings do exist, most of them of slaves, often from the African continent. There are a few that have a South Asian or Asian look to them, and you can see that in the captions. They did exist, it’s just those paintings didn’t become famous. It wasn’t that they weren’t allowed to be main characters, they were just never considered. My characters are also challenging what society considers important and who they see as worthy.

There’s also a hierarchy in your book, where race cannot be untangled from class.

I read a document about that hierarchy of colour, which showed that for richer families, it was up to them how much they wanted to accept mixed people into their family. While the mixed person might have been elevated through class, they'll never be at the same level as someone who's ‘pure.’ It draws attention to the shallowness of people at that particular time in 1890.

Have you noticed any stereotypes around mixed identity, present day or historical?

There’s a stereotype where mixed means half-white and I think we are slowly moving away from that, which is a good thing. There’s also this idea of an inherent hierarchy that links to the lightness or darkness of skin tone. I can’t comprehend how we’re in 2025 and the lighter you are, the more accepted you are.

I’m almost pre-empting how someone is going to tell me that I’m trying to change history with my book. I'm not trying to change history, I’m not pretending mixed-race people were the most important in the room, I’m just trying to unravel some of those truths that were hidden out of necessity, not a plot device. There’s a necessity to shed light on these stories because they’re human experiences.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

My identity is not definable, and that opens some really wonderful conversations. It’s made me open as well in terms of perspectives and how I approach things, because I don’t expect to totally fit things into boxes.

Can you sum up your mixed identity in one word?

Grateful – I'm really grateful, especially in my adult life. You take it for granted when you're little. I'm really grateful for the backgrounds of my parents and the experiences that came with that and the awareness it’s brought. Hopefully I share that with my children.

Buy The Portrait Artist here. Next week, I’ll be speaking to model and Made In Chelsea star Paris Smith. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Shop Mixed Messages tote bags and bookmarks on Etsy now!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.