Jordan Stephens and Beth Suzanna: “I wonder what it’s like being only Black”

The author-illustrator duo on acceptance, cultural norms and the madness of mixedness

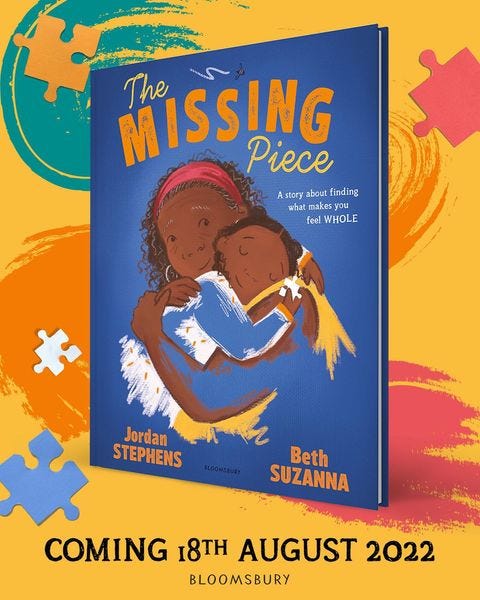

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week I’m speaking to actor, musician and now author Jordan Stephens and illustrator and designer Beth Suzanna. Both Jordan and Beth are of Black and white heritage, and have just released their first children’s book, The Missing Piece. The story follows Sunny, a girl on the hunt for a missing jigsaw piece who comes to realise that maybe the journey is the destination. Read Jordan and Beth’s stories below.

How do you define your racial identity?

Beth: I like the term mixed-race. I’m half-Black Afro Caribbean and half white.

Jordan: Salt water brown. It’s complex, I don’t know. I just feel brown. As a kid, I always thought that the term coloured was a real compliment, I couldn’t get my head around the fact that people wanted to not be full of colour. Mixed-race seems the most fitting.

I feel like as mixed people, we’re given this language that we don’t actually love. It’s just so other people understand us.

Jordan: I think being mixed-race is really, really, really hard. I think people are fighting for oppression attention, or for their voice to be hard and say “this is how difficult I’ve had it.” For some people, it’s important to have a space to explain the difficulties of being, but for whatever reason, the mixed-race experience I find so baffling and confusing that I actually would rather not think about it.

I’ve been told that being mixed-race is a privilege, and it has been a privilege to be light-skinned. I’ve been told that I’m seen as less threatening and have more opportunity, which is definitely a possibility, but if I’m half and half, it’s weird to me that I never get to choose. I couldn’t be white if I wanted to.

Beth: I’m light-skinned, and people like to use the term white-passing but I don’t like that. It reiterates white as the default. That has definitely allowed me lots of privilege. My sister has darker skin, and I’ve seen how she’s moved through life in a different way. It’s weird, acknowledging the privilege that you have but also feeling a disconnect to other spaces. You’re in a middle space, which can be really hard to navigate.

Have you gone on a journey with the way you’ve felt about yourselves throughout your lives?

Jordan: Yeah. I used to hate being Black when I was a teenager. I don’t know whether it’s to do with the time or location – I was one of a handful of Black kids in my school in Brighton. I think it’s difficult to be a young person living outside of London that’s Black and goes through the school system that doesn’t come out with some kind of white supremacist ideas. Everything you learn, whether it’s history or medicine or whatever, is centred around white people.

Then there’s the idea of what is deemed attractive and presentable. I internalised that self-hatred. Now with my dreads, the way I feel with them is really trippy. I suddenly feel like I’m battling these ideas of what dreadlocks mean, like dirty or not presentable. It’s wild, I shouldn’t be feeling like that. It’s old school shit. The journey is a tough one. Do I feel totally accepted by either side? I don’t know. Should I even need to care about that?

Beth: I used to straighten my hair to within an inch of its life. Growing up in a predominantly white area can confuse you as a child. Lots of the representations that you’re seeing don’t really reflect you or your experience. It’s isolating. Going to uni, you think more about your identity when you move away from home and are in a new city.

Jordan: I think it's understandable for any person in an environment where you're a minority to try and blend into the majority. But it is tough in terms of finding identity and authenticity. I find cultural norms confusing, like what’s a Black or white way to behave.

Beth: In one of the spreads in the book, there’s a character, Gabriel, with two Black men. They’re shown washing and drying their little girl’s hair. It was really important to represent stuff like that. My dad is one of the most gentle, nurturing people I know, and for me it’s a no brainer that Black men are like that. But I guess lots of people haven’t seen that representation before, so it’s nice to include little nods to it in a children’s book where it’s not the whole narrative. It carries just as much weight when it’s just a part of the story.

It sounds like you have a great relationship with your dad – did you ever talk to your family about being mixed?

Beth: No, my dad and I haven’t had that discussion – there have been little comments though. Me and my sister, and me and my grandma do.

Jordan: I wonder how my mum felt. She was very encouraging for there to be a connection between me and my Caribbean family, but my mum has limitations being a white woman. I vividly remember the first time I saw racism on a film on TV, and I could not understand it. My mum had to explain it to me, it was dark. The injustice was too much. My favourite artist was Sisqo, and I kept thinking he was saying “knickers,” so my mum had to explain that. It was an awkward time, stumbling through that.

I know more about my dad’s experience, as a Black man in the 70s, but it’s not my personal journey. That's one of the funny things about being mixed-race is that I have a unique experience to both of my parents. I wonder what it’s like being only Black.

How have you connected with your heritage?

Beth: Rice and peas is a traditional Caribbean dish, and we’d have it with roast dinner. I told people at school and they said “ew,” I just thought it was normal.

Jordan: Put me on death row, jerk chicken, rice and peas…

Beth: Ackee and saltfish.

Jordan: Plantain, dumpling. It’s just the best. I don't know if that's how I feel connected, but I have to have Caribbean food and I love spice.

Beth: Only recently have I said to my dad that I want to learn how to cook rice and peas. He says there’s no recipe, just when it smells or bubbles like that, you know it’s done.

Jordan: It’s just vibes.

One of the key things I’ve learned from writing Mixed Messages is how being mixed has impacted people in less tangible ways – is that true for you, maybe in terms of your creativity?

Beth: I’ve not really thought about that before, but I guess there’s a subconscious openness.

Jordan: I suppose an extension of code switching. My mum and my dad had different upbringings and influences, and they’re both feeding into my ideas. I definitely find that one of my advantages in life is the variation of rooms I can walk into based on my life.

I do change the way I talk, and I struggle with that sometimes. A previous partner asked me which version of me was the real version. My current girlfriend would say that they’re all the same. I shift, but it’s all me, it’s just different parts of me that play out at different times. On an objective level, I think it can be a strength because I'm not intimidated by certain places. I don’t know if it’s a direct result of being mixed, it’s such an odd space.

Beth: I think we’re all only just starting to figure it out and unpack it.

Do you think there’s a stereotype of what it means to be mixed? How do you want the conversation to develop in future?

Jordan: I have this sweatshirt that says “too white to be Black, too Black to be white.” That’s just what it feels like.

Beth: I think it’s people having an understanding that there’s so many different ways to be mixed. Mixed people are all different colours, shapes and sizes. No two mixed-race people are the same.

Jordan: The mixed-race conversation is a window into the somewhat boring but very real intersectional dynamics of society. I've been thinking about my teenagedom, I remember being fetishised by a couple of girlfriends I had who dated every mixed-race boy in Brighton. I wonder what that means. I know there’s colourism with dark-skinned Black women, and this idealisation of light-skinned girls is a very complex subject that’s not necessarily to the fault of mixed-race girls or women. It’s reflective of a deeper political ideology and it’s hard to navigate that.

I had an audition earlier for a role that’s specifically mixed-race. The idea of a lead mixed-race man is nearly non-existent, which is bizarre. When I started acting, I used to nick roles off white actors. That would be advantageous I suppose, being mixed-race and seen as not too far off the mark. But when there was a push for diversity, it went the whole other way and it was just dark-skinned Black men. You could name five or six incredibly successful dark-skinned Black male actors, but you can name maybe three mixed-race lead actors of all time. It’s a weird glitch, I don’t know why, it’s not the same for women.

I’ve seen conversations online where people have suggested to mixed-race men to check their privilege, and I’ve had conversations with mixed-race male friends who say this is so weird because in this particular space of acting, lead male performances, there’s no privilege there. It’s probably something to do with what's considered to be feminine and masculine, appealing and romantic. The fetishisation and over-masculinisation of Black men, the idea of Black men being brutal leaders… it’s deep shit. On the other side, you’ve got mixed-race women playing dark-skinned Black women.

It’s difficult sometimes to say what white even means. Does white mean not Black, or does Black mean not white? Whiteness as an idea is confusing to me too. Then everyone fake tans. It’s very confusing. I think mixed-race people should have WhatsApp groups of support. I think there should be a specific space for mixed-race people to support each other.

We often talk about the confusion about being mixed, but what’s one of the best things for you?

Jordan: I just think Caribbean and African culture is such a vibe.

Beth: I would say that openness and understanding of other cultures. Speaking to people that are mixed in other ways to me, we’ll have similar experiences. You’ve got more openness to things outside of your own experience because you were raised between the two. Most mixed-race people I know are open. There’s less judgement I suppose.

Jordan: There’s definitely a positive to having two different worlds and cultures. Loyle Carner says it’s a mad one historically being of African diasporic and British heritage, but you get to experience different ways of life and go into rooms you may not get to go into. I love that I have that connection to rice and peas, dancing and singing.

Can you sum up your mixed experience in a word?

Beth: Ever-evolving. You’re learning more about yourself and the way you see yourself. The older I get, the more I’ll understand my identity and who I am. Ever-evolving in terms of there being more mixed representation out there as well.

Jordan: Infinite. It feels like being mixed-race is the result of circumstances beyond whatever humans want to try and trap each other with. It’s an amalgamation of morality and culture and colour and geography and that collaboration, merging, mixing, blending will always happen, forever.

Buy The Missing Piece now. Next week I’ll be talking to author Kit de Waal. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Next week is Mixed Messages’ 2nd anniversary, so keep your eyes peeled for a special giveaway!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

I love this idea from Jordan about creating a Whatsapp group for mixed people. There has to something like that out there already...anyone know of one? If not, we should start one from Mixed Messages!!