Kaliane Bradley: "There is so much space, so much capaciousness"

The author on assumed identities, Cambodian culture outside of her family and her urgent curiosity

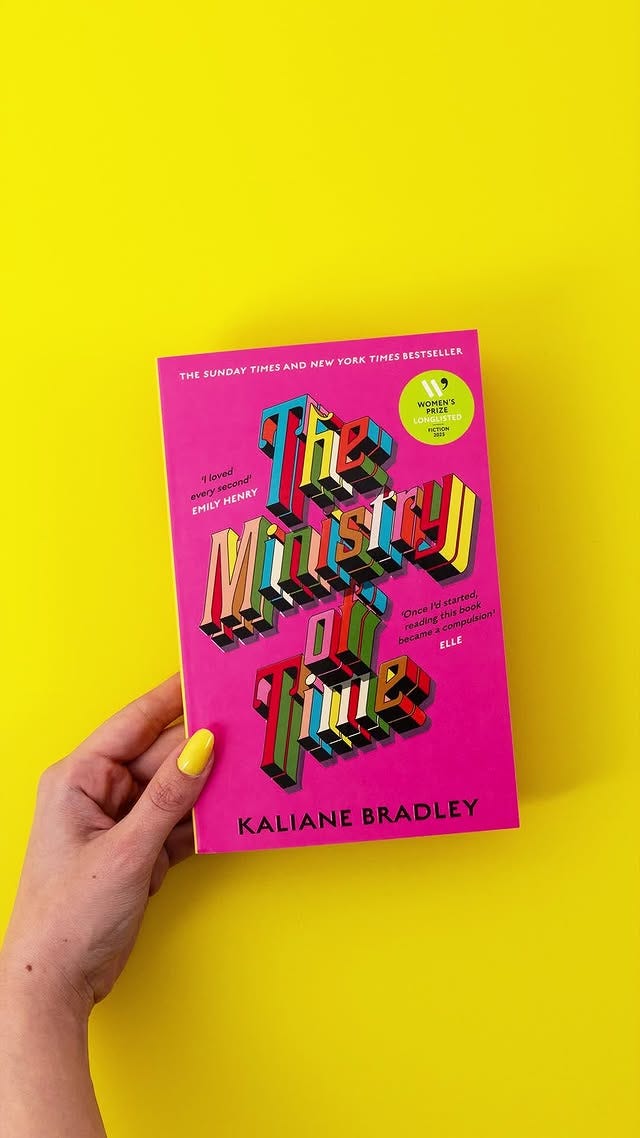

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week’s guest is author Kaliane Bradley, who is of mixed-Cambodian and white British heritage. Kaliane is the Women’s and Jhalak Prize-longlisted, Waterstones Debut Fiction shortlisted The Ministry of Time – and that’s only the awards I could fit in. The debut follows a civil servant working in a mysterious new government ministry gathering 'expats' from across history to test whether time-travel is feasible. But when past choices and imagined futures are confronted, can love triumph over the histories that have shaped them? It’s an incredible read, and I couldn’t wait to hear how Kaliane’s background fed into the characters. Read her story below.

How do you define your identity?

My dad is white British, my mum is Cambodian. Specifically, she’s Khmer. I refer to myself with a hyphen as British-Cambodian. The hyphen, for me, signifies the sense of mixing rather than British being a modifier for Cambodian.

In my book bio, I’m described as a British-Cambodian writer, which is something I asked to have included. I went back and forth, wondering whether I needed to signal that I’m British-Cambodian. My identity, as is the case with everyone, has impacted the way that I perceive the world and, consequently, what I write. Including that in my bio isn’t to prove anything, but is a statement of fact about where this book has come from.

My mother’s experience of Cambodia was non-typical – people don’t necessarily imagine her life as it was. They were bourgeoisie. In the wake of the Khmer Rouge, it’s very easy for people to assume that being a Cambodian refugee means you were a rice farmer fleeing through the forest at the edge of the border to get to a Thai refugee camp. That wasn’t the case.

Your book also references the misconceptions of what a refugee is – can you tell me a bit about your mum?

When I started writing the book, the bridge, the main character, wasn’t British-Cambodian. When I was thinking about the thing that had been most resonant for me as I built up these characters, it was their journeys from the past, the ministry snatching up these ‘expats,’ as they call them, from the past and into the 21st century, telling them they can't ever go home again and that they have to assimilate – use the right language, dress properly, have the right ideals and be productive, be good British citizens.

The psychological and interpersonal situations I put them in clearly parallel a refugee journey, someone being pulled from a country that they can never go home to and being told to be grateful to the British government who saved them.

The bridge is someone who falls in love and chooses to be complicit with power. She makes a series of quite difficult decisions to not show solidarity, so I thought that she needed to be a bit more than a cypher that anyone can project on to. Those things are very personal, so she needs to be a more fully rounded person because the book is partly about the legacy of British imperialism.

She's a character I find interesting in the context of trauma and control. Quite a lot of what she describes of her family's own experience of Khmer Rouge is not taken from my family story at all. Her story is more recognisable as a refugee story. My mother was in the UK already and then just could never go home.

In my second book, there’s another mixed-race Cambodian woman. She’s not the main character, I just have to put a mixed-race Cambodian woman in everything I write. She talks about how white people have a really specific idea of how they are able to ennoble themselves in contrast to her story. It’s either the rice farmer with seven kids and too much religion or the doctor or professor in the original land who has been forced to become a security guard. The character’s like, “my dad was just some rich dickhead who played guitar who ended up in the UK,” and then realises “oh shit, turns out I'm a wretched brown person. I thought I was just a person.”

How has your Cambodian identity flexed over time?

It does change, not only the way that other people understand you but the way that the narrative about an ethnicity that you are part of has changed. My understanding of Cambodia and the Cambodian community has changed. When I was a child, Cambodian just meant my mother, my aunts, my uncles, it meant my family.

Everyone's family is completely idiosyncratic and complicated, threaded through with these strange personalities, rivalries, loyalties and loves. When I started moving outwards, away from just thinking about my identity as being something that's part of my family, it made me curious about what I meant when I described myself as Cambodian.

My family was very privileged and some of them survived because of that. If I’d grown up in a Northern town, that would have impacted my identity enormously. It's been interesting, that push and pull between the ways that I am marginalised, the ways that I am privileged and the ways that I have to think about identity.

What were your cultural touch points growing up? Food is a theme throughout the book.

I can’t help it, I love writing about food! My mother was encouraged not to speak Cambodian, but obviously it was really important for us to have connections to the culture so I was brought up as a Buddhist, like most Cambodians are culturally.

I did a lot of ballet when I was a young, and I also did a lot of Cambodian classical dancing. They required completely different postures and movement qualities. My family also knew a lot of musicians at the time, so that was something I was encouraged by my mother to engage with.

Because my mum came from a middle class family, she was sent to a French school. My family all speak French, most don’t actually speak English. My mother’s the only one who emigrated to the UK, everyone else emigrated to France and Belgium. The influence of French culture, French chic, French manners and French traditions are hugely influential and so deeply ingrained in my mother and what she taught us. A lot of the traditions and foods that my mother passed down are not entirely Cambodian but French-inflected, which was really interesting to discover.

We’ve spoken about you ‘passing’ as white, which I wouldn’t necessarily say that about you. Do you want people to see that you're Cambodian?

It’s been hugely important to me to be recognised as mixed-race and Cambodian. Another reason I wanted it in the bio is because it is so important to me, it has been so influential to the way I think and the way I exist in the world, the way I write. It makes me so glad when someone can see me.

The sense of me passing as white is a very London thing. Because this is such an ethnically diverse city, people don’t necessarily notice or clock me, or care. Every single time I’ve moved into a space that’s predominantly white, particularly in countries where there’s quite a monolithic ethnic makeup, it's amazing how I often get mistaken for Chinese – I know this because people sometimes shout slurs at me.

Have you noticed any stereotypes around mixed people?

At university, a man started making fun of the food I bought in a supermarket, then asked “where are you from?” I was so unguarded – at university, everyone on my English Literature course was white. I’d come to the course without a political consciousness. I didn't really have a sense of thinking about the liberation of marginalised identities because the bubble of privilege I'd lived in made my life simple.

I was so unguarded – at university, everyone on my English Literature course was white. I’d come to the course without a political consciousness. I didn't really have a sense of thinking about the liberation of marginalised identities because the bubble of privilege I'd lived in made my life simple. I just told him that my dad was British and my mum was Cambodian, then he asked “did they meet on an army base?” I realised he’d just decided I was the illegitimate Madama Butterfly child. It was so weird, the assumption about what my parents were like and therefore what I was like. I don’t like that at all.

One of the turning points in the way I thought about my identity was after I read America Is Not The Heart by Elaine Castillo. She talked about the way identities are often put as contiguous to whiteness, but we’re global majority people. Thinking about my own internal expression of identity and my contiguousness to whiteness and privilege, but also my contiguousness to community and diaspora. I think those are really interesting, and I'd like us to have a little bit more flexibility in that. Class is a really interesting thing that we don’t talk about enough yet.

What's the best thing about being mixed for you?

I wouldn't change me. I wouldn’t change anything. I'm very happy with who I am. I’m very happy with people misunderstanding me, I’ll take it. I love my family, I love what I’ve learned about my English and Cambodian cultures, which are very different and which I feel like I learn more about every day.

Being mixed-race has encouraged me to feel curious. There’s so much I want to know about myself and my background that if I wasn’t [mixed] I wouldn't have that same urgent curiosity to find out. It would just be with me, I’d just be single and whole. It’s made me curious and that’s a really happy thing.

How would you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

Ever-expanding. Even in this conversation I feel like I’ve thought about a new facet of identity. I love the fact that it just keeps expanding. There is just so much space, there’s so much capaciousness.

Next week, I’ll be speaking to River East, River West author Aube Rey Lescure. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Shop Mixed Messages tote bags and bookmarks on Etsy now!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

Not the point of the article but Kaliane's main portrait - so gorgeous.