Lucy Fulford: “My work has stemmed from feeling a little off-key”

The author and journalist on owning her story, cultural guilt and seeing racism in black and white

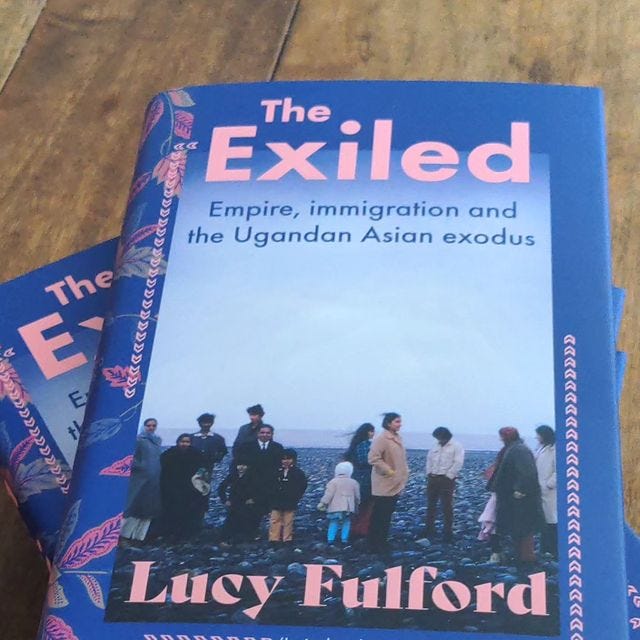

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week I’m speaking to journalist and author Lucy Fulford, who is of Indian and white British heritage – although there’s a lot more to it than that. Lucy and I share a very similar background, with our Indian families having grown up in East Africa. It’s an experience she explores in The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and the Ugandan Asian Exodus, a book that delves into the global diaspora. Read her story below.

How do you define your identity?

I used to say half-Indian, half-British, although I was born in Australia which complicates things. My first answer was always Australian, and I do still feel Australian, even though I neither sound nor look it. You get off on the wrong foot in a conversation like that.

These days I don't tend to say ‘half,’ I feel like it was reinforcing the idea that I wasn't enough of anything and disenfranchising me from having a stake in either country. Now I say ‘my mother’s Indian, my dad was British, I was born in Australia.’ That leaves out the African side of things – for ease, not because I don't feel connected to it. If it’s a longer conversation, I’ll say ‘my mum’s side of the family were in Uganda.’ That can blow people’s minds once you start talking about four countries.

It’s interesting you use the term ‘get off on the wrong foot’ – how do you feel when someone asks about your heritage?

It's definitely changed over time, and I’m sure it will change again in future. I used to be quite hostile when I was younger, cycling through saying I was Australian and English without mentioning the colour of my skin. I always presumed it was antagonistic and often it wasn't.

Now, I’d presume that people are curious. It depends on who’s asking, the tonality and the context. If someone is clearly just wanting to get to know me, then I’m really happy to talk about it. Other times, they might phrase it badly. I don’t think you can’t ever ask someone brown where they’re from, only you will know when it feels off.

Have you felt connected to all of your backgrounds?

It does feel quite piecemeal at times. That can feel really nice, like you’re picking and choosing the things you want to explore or celebrate and taking the best from all of your different reference points. Sometimes I can feel a bit guilty, wondering if I’m cherry-picking the highlights and not interacting with more challenging parts of each culture.

There’s obviously no strategy as to how to combine your heritage, it just comes along naturally. I feel more Indian in some environments, more English in others. I don’t speak any Indian language either – one of the first questions I get is “do you speak Hindi?” when my family language is Malayalam. I grew up in Sydney, a multicultural city with a huge East Asian population, so those are my childhood reference points and Australian culture too.

When you’re in the diaspora, generations down, I think you do want to be able to connect to some of those reference points. The second time I went to India was the anniversary of my dad’s death on a spontaneously booked yoga trip. My dad was English so yoga wasn’t related to him, but something about that period of flux made me want to connect with my past. Looking back, I can see I did want to connect with something Indian, but not fully. I didn’t go to Kerala, which is where my family are from, so it was baby steps.

Has your sense of self been a fluctuating experience for you?

Definitely. When I was younger and around my grandparents, we had a lot more of the food than when I came to the UK. I moved from a much more mixed society to a white majority area when I was a teenager, where you don’t want to be different. I was trying to ignore my Brownness. Learning about Uganda has been a slow burn over the past ten years.

Was learning about your East African heritage a conscious decision?

As a journalist, I actively avoided stories to do with diversity or minority issues to not get typecast. But I eventually reached a point where I couldn’t ignore my Ugandan Asian history. I’ve been interested in it since I was a child, and I wanted to weave together people’s stories to make it more current. I wanted to look at how the next generation of people feel about this identity and how the colonial past still reverberates.

I’ve often felt like a fraud talking about being East African Indian, even though it is my heritage. Have you ever felt like this wasn’t your story to tell?

Completely. One of the reasons I didn’t touch this subject for so long was because I didn't feel qualified to. My family isn’t deeply embedded in East African Asian communities today. I definitely didn't feel like I was someone that could have a voice on this – I can’t remember at what point I decided I did.

After working on this book for a number of years, now I do feel confident in my place talking about this history. It was a massive process to get there, it's a bizarre level of race related imposter syndrome. When interviewing people, it was like an immediate entry pass into conversations when I said my family left Uganda. That grew my confidence.

During your research, you found a document that said people of ‘mixed blood’ weren’t desirable. That hit you quite deep when you realised it was talking about your family.

These words looked very stark in black and white. There was also the White Australia policy... The thing is, it’s only really finished in the decade before my grandparents went to Australia. They were some of the first immigrants who could freely go there, not being white. It’s all eugenics, purity of blood stuff, and it feels really uncomfortable knowing they were explicitly referring to people like my family in that very close time period.

Did you ever speak to your family about being mixed?

I haven't particularly. I've had more conversations with my mum over the past couple years. When her and my father got married, there was a conversation of whether they wanted to be in a mixed relationship and if it would make their life more difficult, the presumption being that it would. I don't know how much that then filtered down to how their children's experience would be, but those conversations were definitely happening at that point in the ‘70s.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

Most of what I've done in my life is probably because I'm mixed. My work has stemmed from feeling a little off-key. That lends itself to being a journalist, someone that observes other people and is interested in other people’s stories.

I think being from so many different places has made me really curious about the world and have that big picture view on our histories and what happens next. It feels like a privilege to have lots of influences in my life.

It’s definitely a cliche, that caught between two worlds stuff, but I probably felt not quite enough of anything. I don’t feel like that anymore.

Can you sum up your mixed identity in one word?

A gift. I'm not trying to sugarcoat things, there’s challenges around it, but it’s a gift.

Buy The Exiled on Amazon, Bookshop or anywhere you get your books. Next week I’ll be speaking to author Hanako Footman. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday.

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

This was very inspiring and educational.

“Most of what I've done in my life is probably because I'm mixed. My work has stemmed from feeling a little off-key.” This really rang true for me and I also think that it is a process that can take decades of work and gradual reflection and realisation.

Congrats on the book, Lucy! I'm a three-country person myself, and yes, it can get complicated, because the country where I grew up--France--is not the country of either of my parents (US and India). So I feel I am from France, but I'm not French. But I'm fluent in French. And I have an Indian name, but light skin and eyes. I understand a lot of Bengali, but I don't speak it. I speak Spanish. My answer to where I'm from really varies, like yours, depending on who is asking and how much they really want to know. And how much time we have to talk about it!

I, too, wish most things were less categorized. Pretty much all my career has been multi-disciplinary, and my second historical novel, now in the hands of my agent, has a part Indian/Muslim, part French/Catholic young boy at its center. And now I'm starting a publishing company, Galiot Press, to publish books that defy categories and that blur lines.

All the best with the launch of your book.