Nadeine Asbali: “I will always be an outsider to both parts of me”

The author on realising her difference, nostalgia for Libya and her otherising defence mechanism

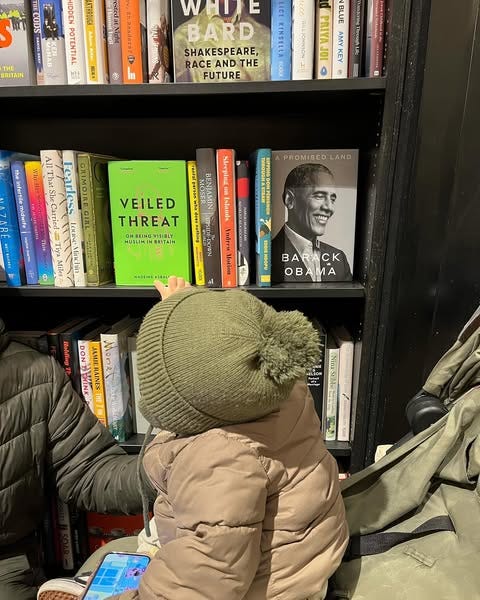

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week, I’m speaking to author Nadeine Asbali, who is of mixed-Libyan and white heritage. Nadeine’s incredible book, Veiled Threat, is a vital examination of what it means to be a visibly Muslim woman in Britain. Deciding to wear the hijab after a summer in Libya, Nadeine returned to find that she was now seen as sinister, perverse and foreign. Veiled Threat is a must-read – and a perfect Christmas present, might I add. Read Nadeine’s story below.

How do you define your identity?

I tend to just say I'm half-Libyan, half-English. Sometimes I’ll say half-Arab, half-white. If someone asks and I can tell they’re being racist, I'll just be like, “I'm English” because they’re trying to make a point. When I’m in brown circles, I’ll just say that I’m Libyan. I don't always even mention that I'm half English.

Other Mixed Messages guests have said that ‘Arab’ feels like a very politicised term – does it feel that way to you?

I don’t think I would say Arab in a white space. I tend to say Arab with other brown or Black people, it feels safer. They understand that I’m talking about being Arab geographically rather than linking it to all these ideas of Arabs being terrorists.

When my dad came to Britain, it was around the time of the Lockerbie bombings, so being Libyan was synonymous with being a terrorist. His generation would sometimes say they were Italian because Libya was colonised by Italy, or they’d just say they were Arab. I don’t think my generation has those connotations, although ‘Arab’ in general does now.

Do you feel a strong connection with Libya and Libyan culture?

Growing up, we used to go every summer for the whole summer. I did feel really connected to it. When we were in England, my dad was quite strict with us – we couldn’t go to sleepovers or play in the street. In Libya, they wouldn’t see us for six weeks, so I associated it with freedom. I associated it with a lot of positive things I wished I had the whole year round – we’d go to the beach all the time, I had a massive family there, whereas here I just have one sibling…

After the Arab Spring, we stopped going, and then over the years I don’t have that same connection to it. I have a nostalgic connection, but I haven’t visited for fifteen years. It's sad. At the same time, I've probably taken on more cultural influences as I've gotten older than I did as a child. I have a young son, my husband’s Pakistani so his only Libyan influence is me and my dad. I feel responsible to instil some Libyanness in him. I speak to him in Arabic and feed him Libyan food. That has resurged my Libyanness a bit because I don't want him to feel no connection at all.

Most of Libyan identity lies in food and language, so sometimes I feel like they’re the only ways I can cling to it. Even my Libyan Arabic isn’t great. Language can be so isolating. In Libya, I would be able to grasp what people were saying, but I was shy about speaking because I knew I had an English accent. They would fully laugh in my face. I still am shy about speaking it, but after having my son I realised I need to around him.

You write about your decision to start wearing a headscarf as a teenager – how did the way people perceive you change?

At first I felt English. I knew our dad was foreign and did things like prayed and fasted, but me and my brother didn't feel particularly foreign ourselves. It was just a bit of a quirk that we had a Libyan dad. As I got older, I started to feel more isolated from all the kids. I grew up in Northampton, which was a very white town. I went to a really white primary school and as I got older, I started to realise that I was different to the people around me who I thought I was the same as.

It was partly because I wasn't allowed to go to sleepovers and stuff like that, partly because I had black hairs on my legs in my checked summer dress. Year Sixes are brutal. In secondary school, it got more pronounced. Then I had a bit of an identity crisis. I thought that I had failed in being English, which is what I thought I was, so I thought ‘let me try and be the other side of me now.’ As a family, we’d been English when we were here and Libyan in Libya. That wasn't working for me anymore.

I came to start wearing the hijab because I was trying to be Libyan. Looking back, I was trying to visibly otherise myself as a defence mechanism. To almost say, ‘well, I'm not trying to be English, so you can't say I'm not.’ I didn’t expect how everything would change dramatically and immediately.

As soon as I landed on British soil, the hostility from airport staff and the counter terror apparatus coming at me as a 15-year-old was really disorienting. Then in school, my teachers and friends treated me differently. What that did for my racial identity was make me feel even less white and less English. I was trying to be more Libyan, but that didn’t work either. What it led me to is to identify myself as Muslim, because that's something I felt like I could be fully. It was a slow realisation.

Have you noticed any stereotypes around being mixed?

Growing up, being mixed-race just meant half-Black half-white. I would never call myself mixed-race because it felt like a very specific label for a certain kind of mix. I think there are lots of stereotypes about if your mum is white, then you’re not a real whatever your other side is.

Everyone has elements of difference that come together within them, I wish people didn't see it as such a big deal. If your parents happen to come from different countries, that doesn't define who you are, and at the same time, you still have every right to both sides of you.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

Because it gives you an outsider status in a negative way, it also gives you the freedom to view both of your cultures from the outside. When you’re so embedded in a culture, you can’t necessarily see what's wrong with it. When you’re mixed, you can see both for what they are because you're an outsider to them.

I can see really good things about Libyan culture, I can also see the bad things that I don't want to pass on to my children. I don’t resonate much with English culture, but I’m more English than I like to admit. The nice thing is you can pick and choose which parts you want to adopt and celebrate, and which parts you can criticise and stay away from.

Being visibly Muslim has complicated my identity more, especially as a mixed person. In the eyes of the state, especially in a country like Britain, we're just defined as Muslim. The nuances about ethnic identity almost don't matter. When people have another element to them that they’re defined by, the mixedness gets lost.

Can you sum up your mixedness in one word?

Outsider. I will always be an outsider to both parts of me, which can feel really isolating. At the same time, I can define for myself what my mix means to me. I’ve always felt like I had to prove I was really Libyan.

Next week, I’ll be speaking to my final guest of the year, creator Demi Colleen. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox the following Monday. Shop Mixed Messages on Etsy now – the perfect Christmas present!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.