Nicky Weir: “Kids at school couldn’t understand how my dad could be white”

The makeup artist on how food takes her home, the unsaid mixed understanding and feeling disconnected from her Irish roots

Hi, welcome back to a delayed Mixed Messages (due to a nasty virus!) This week I’m speaking to makeup artist Nicky Weir, who is of mixed English, Irish, Vietnamese and Sri Lankan heritage. I first met Nicky while working on a project with Graduate Fashion Foundation, and was enamoured with her wide smile and positive energy. Her stories of her Vietnamese family had the whole crew laughing, and I knew I needed to find out more. Read her story below.

Can you tell me a bit about your background?

I’m Vietnamese, English and Irish. I would definitely say that I’m more Vietnamese because I was more raised by my mother’s side of the family. It was a very difficult culture and upbringing. My father had a different viewpoint – he’s an aristocratic public schoolboy, very English and regal with an Irish mum.

I’ve always been proud of my mother’s heritage because they embraced us, we’re all together as a tribe. Her mum was half-Sri Lankan. I was born [in England,] but my parents split when I was five and we went to Singapore. It was the best time of my life, it felt like in The Wizard of Oz when you go from black and white to colour. Because I’m deaf, I’m more visual – everything was so colourful, lively and joyful.

We came back because there were no schools at the time for hearing impaired children in Singapore. We went from technicolour to black and white. I remember being quite traumatised, thinking “why are we here? Everyone’s so miserable, it’s so cold, it’s not welcoming.”

What was your experience like growing up?

When I was about eight or nine, kids at school started calling me “ching chong.” I’d get racist comments and make fun of. I couldn’t understand that. Then when my mum came to school, their jaws dropped. They accepted her because she was beautiful. It was really strange and wrong. The kids couldn’t understand how my dad could be white. At the time, there weren’t that many mixed kids.

My dad was living in LA at that time, and when I’d visit he’d introduce me to his friends as his daughter. I remember lip-reading one woman asking my dad if I was adopted. When he told her my mum was Vietnamese, she got really embarrassed.

Recently I met my Irish cousins – it was overwhelming, a bit like Long Lost Family. I felt disconnected from them. I only had my father and my Irish grandmother, who isn’t with us anymore – I was really close to her. She embraced us more than anything, calling me her ‘lotus blossom,’ which is my middle name. But my cousins kind of said “she doesn’t look like us, but isn’t it great” and that was wonderful.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more and more proud of my heritage, more so since my mum passed. That Vietnamese and Sri Lankan culture is closer to my heart than anything else. Now people say “you don’t look Asian” but I say “I am! I’m half!” It's really weird to navigate that sometimes.

How did your parents meet?

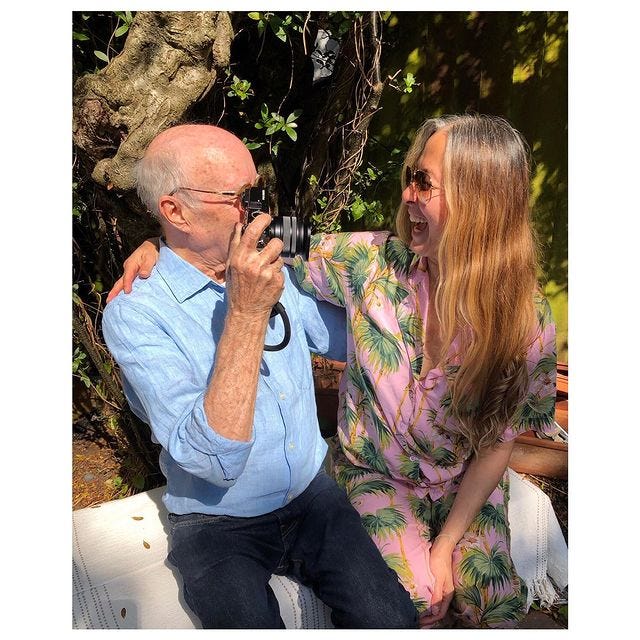

At college – he was doing photography, she was doing art. My grandmother emigrated over here because she said “I have three beautiful daughters, I want them to get a great education in the UK and when we go back to Singapore they can marry good Asian men. Did that happen? No. One married an Irishman, one married an Englishman, one married a Scotsman.

Did you ever speak about being mixed with your family? A lot of people I’ve interviewed never did, myself included.

My mum, her sisters and my grandmother would all speak Vietnamese – I love the sound of it, but I can’t understand it. They tried to teach me but I have a bad enough time trying to speak English. When we were kids, we’d make fun of the sounds, but they’d rip us to shreds and say “don’t you dare make fun of our language, that’s where we’re from.” As kids, you don’t think like that. They told us to be proud of being Vietnamese and Sri Lankan.

You’ve spoken about food, customs and language, how else did you connect to your Vietnamese culture?

I love and respect their values, ways of thinking and reasons for how they do things. I immediately feel connected when I meet other Asians because we have similar customs and respect for other people. It’s an unsaid understanding.

Living in Singapore had a massive impact on me too. The smells, the food, the humidity… whenever I go to Thailand and feel that humidity or smell something in the market, it takes me home to my family who are no longer here, like my mum and my grandmother. It’s almost like my memory pod.

How would you like to see the conversation around mixedness develop?

We’re the first or second generation of mixed-heritage people, back in the day there weren’t many of us compared to now. People are a lot more open-minded and not as racist now… maybe, perhaps. Back then it was unusual to be in a mixed relationship, now it’s normal. We should continue to talk about mixedness, so many layers come into that conversation. Our experiences are so different, but what we can definitely say is that we share an immediate understanding of who we are as a mixed tribe.

Do you think your mixedness has impacted your career as a makeup artist in any way?

When I work within models, I can tell straight away if they’re mixed. People will ask me what my mix is as well, I love it. I always say Vietnamese first, then English. I definitely think that when I work with models of colour that they kind of trust me more straightaway. White British people may say that that’s a bit racist, but people of colour will get it. It’s an unsaid, immediate understanding.

We often talk about the downsides to being mixed, but what’s one of the positives for you?

I love the food. The fact I can have a bowl of curry for example and it makes me think of my grandma. A flood of colourful memories. It takes me to that place of comfort, to home. Lychees take me to my grandpa climbing up a tree and getting them for me. The smell of a Vietnamese restaurant makes me think “these are my people” straight away.

Only when I got called names in primary school did I think “maybe I should be white, I’d like to be white,” then I remembered feeling really ashamed and guilty for thinking that. When I got to secondary school, I thought “no, this is me, like it or lump it.” I’ve always been a positive person.

I think it’s very important to embrace your identity. We know about the British side because we’re living here. We are not in the land of our mothers, so that’s why we ask questions. I asked so many questions, they drove my family mad but I’m glad I did because they’re not with us anymore. You want to have the freedom to do whatever you want with what you’ve learned from your culture. I choose to continue cooking Vietnamese food and eating with my friends – that’s my love for my family continued through sharing food with my friends.

Can you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

Vibrant. It vibrates within your soul, it’s vibrant in terms of colour, the connection and culture is just vibrant.

Next week I’ll be talking to musician Poppy Ajudha. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday.

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed