Sophia Thakur: “I've never thought you can be half – I’m 100% Asian and 100% African”

The poet on unfair stereotypes, the power in her DNA and liberation from fear

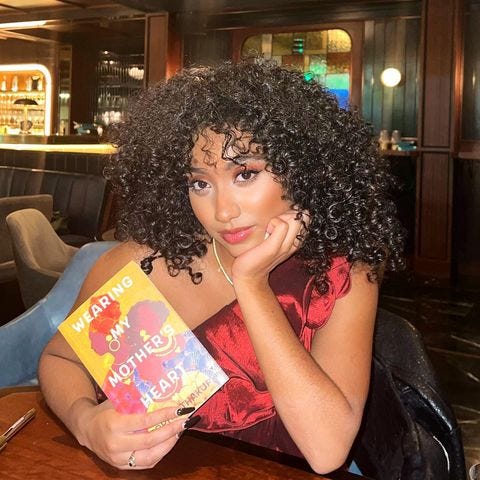

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week I’m speaking to poet Sophia Thakur, who is of mixed Gambian, Indian and Sri Lankan heritage. Sophia’s new poetry collection, Wearing My Mother’s Heart, speaks from her multiple heritages and these poems will hit hard for so many readers. I’ve had the privilege of interviewing Sophia before and was thrilled to explore her mixed heritage in more detail for this newsletter. She speaks so lyrically and it is my pleasure to present her voice for you. Read Sophia’s story below.

What’s your family background, and how do you like to define yourself?

That’s definitely evolved over time. I grew up just saying Black because the time of nuance and dichotomy, even the time of mixed-race, wasn’t really a thing. When I was in secondary school, you were either dark skinned or light skinned. That was the extent of it. It’s only in recent years that I’ve started to realise that Black might not be completely accurate, not necessarily to me but to other people.

Both of my grandmothers are Gambian, which is in West Africa, and both of my grandfathers are South Asian, so one is Indian and one is Sri Lankan.

The way you’ve thought about terminology has changed, but has your sense of self been consistent?

I've definitely felt differently. Now that I know the nuances of race, politics, palatability and colourism, I'm a lot more careful with the perspectives that I represent. I try to be, anyway. Being mixed-race wasn’t necessarily a conversation we had at home. Everyone was African, and that’s just the way it’s always been.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realised that people honour their labels from a point of survival, respect and necessity – it’s definitely made me more careful. Your labels are given to you – I do feel that mixed-race was a label that was given to me, in a world where actually I would have just gone about saying I was Black because I've never really thought you can be half anything. I’m 100% Asian and I’m 100% African. The idea that you can only combat half of the conversation or exist in half of this culture… it doesn't make sense.

When I speak about being mixed, it’s never ‘these parts of me are specifically Asian, these parts are specifically Black,’ it’s more, ‘my colour is lighter than someone who’s full African because I have this background.’ Maybe I’m yet to fully engage in it because I exist in this Black activist space. I’ve gone the whole way the other way, which is also a thing that a lot of mixed-race people do.

In the society we live in, I think you’re seen as your darker or most visible ‘side,’ and so I guess it might be natural to identify with that side.

We give ourselves these labels, but if we’re thinking about conversations on palatability and colourism, the people giving us labels see everyone as Black. So sometimes when people are fighting amongst themselves, I think we need to realise that to the other side, we all look the same. We might as well just band together and work it out.

I’m assuming Gambian culture was quite present in your life growing up – how about South Asian culture? Is that something you experienced?

It's definitely something I’d like to explore more. I remember being in India three years ago, watching a panel discussion where women spoke about the importance of writing about sex in literature. They spoke so softly, gently and powerfully. If you were reading a script of what they said, you’d imagine them on a podium, speaking more as a protest or rally, but their demeanour, candour and cadence was so soft but still powerful. I think that was one of the first times I realised that something about me that I’d always assumed was because I’m a poet is actually inherent in my DNA. That’s always been the approach I take, come gently, softly and eloquently, but come powerfully. Not to say that that doesn’t exist in African culture, but it’s so prevalent in Asian storytelling.

The times I do spend time with South Asian women, especially writers, I’ve realised how much of myself, my art and my creativity comes from that side. It definitely does feel like they’re filling gaps every time.

So much of our personalities are hereditary. The things that we adopt, the way we speak, the movement of our lips, the shape of our eyes, the things we laugh at… all of these things come from my DNA. I used to get terrorised because of my nose and the size of it and how it sits on my face. I just spent more time around people that culturally share the same noses and I thought ‘actually it’s not so bad, it’s just ethnic.’

Some of your poetry is quite directly influenced by your heritage – Are there also ways your mixed identity has impacted your work in less tangible ways?

100%. This is my first time ever speaking about mixed-race anything. There’s so many things that I do believe are assets to being mixed-race that if you say in a lot of spaces, a lot of the spaces that I operate in, you'll be demonised or someone will say it's a privilege to even say that. Maybe it is, but it’s also someone's existence and you can't remove yourself from every point of your existence because someone has privilege. That's not how it works.

I think when you have different cultures inside you, you’re always going to be more open to someone else’s contentions and duality. It’s definitely made me more curious. As a writer, you have to be curious. To be a storyteller is literally to sit inside the story and try to get as many perspectives as possible and understand the root of them.

Has poetry been a way to explore yourself? Cathartic or scary maybe?

I've never written about being mixed-race or being light-skinned. I would love for it to be cathartic, but I’m scared of it. If I answer that question in two years, I might have a different answer.

If you’re given a platform to talk about Blackness, you’re sometimes scared that someone might turn around and say they picked you because you’re mixed-race and more palatable. It's such an unfair hurdle to come across. Yes, it happens, of course it happens. A lot of mixed-race people around me I see doing their thing are working hard, trying their best and believing in their cause, and that they should then come up against a barrier from their own people because it doesn‘t really feel fair. It’s not something I addressed because I’m maybe a bit too careful, but I like to think that in time I will be liberated from that fear because of the knowledge that I'm not a product of colourism.

I read an interview you’d done a while ago where you shared that someone had told you that you shouldn’t speak on behalf of Black people.

That really did it for me in terms of not speaking about it. At a show in Southampton about seven years ago someone said ‘as a mixed-race person, this isn’t your place to speak on the issue.’ I remember being so taken aback, because I've never heard that perspective before. I likened it to feminism and thought I need men to speak about feminism because we need everyone to speak about feminism. If only women are speaking about feminism, it’s just an echo chamber. I think now we've come to realise that everyone needs to speak about race. That is definitely something I’ve worn, but even if that hadn’t happened, conversations on colourism and light-skinned privilege and all those things would have been enough.

Do you feel like there are stereotypes of what it means to be mixed? How would you like the conversation to move forwards in future?

The stereotype I see the most is that mixed-race people ride the coattails of colour into their success. That favouritism is how they get their success. Maybe that’s the case for some, but to paint everyone with one brush is just so unfair and unhinged. A lot of us don't go in thinking ‘I'm mixed-race, this is gonna be so easy for me.’

In the context of why you would think something's gonna be easy for me, chances are it's because there's someone who's white on the other side of the conversation and you think being mixed-race is an edge up. In some cases maybe it is, but in a lot of cases, I go in with the exact same thinking that you're just gonna see me as Black. You’re not going to see that I have an Indian grandad. So I think that stereotype is grossly unfair and silencing.

What’s one of the best things about being mixed?

The food, straightaway! Beyond the cuisines, the fact that food is central to all of my cultures. Food is the beginning, middle and end of everything. If your aunties are coming round, it’s about food. If you’re waking up, it’s about food. If you go to bed, it’s about if you ate.

Food is also one of my favourite forms of storytelling and one of my favourite connections back to people’s cultures and their lineage – music too. It’s something that reminds me that what is in you is so much bigger than what you see. It's a whole history. I know there's some dishes that I eat right now that I love. If I was to put them in front of an English person, their taste buds just might not appreciate it, you know? I’m so grateful that I’ve got vast and expansive taste buds that make space for everything from a jollof rice to a biryani.

Can you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

Delicious.

Sophia’s new collection, Wearing My Mother’s Heart, is out now. Next week we’ll be talking to artist Genevieve Gaignard. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday.

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.