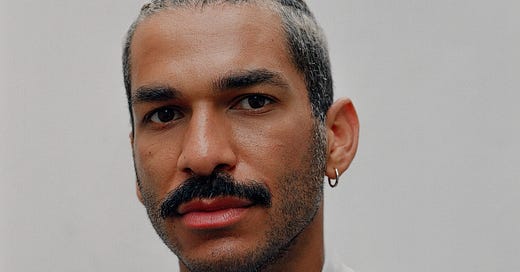

William Hunter: “My experience of my own race is how it is read to me by other people”

The author on unhelpful distinctions, finding kinship and the clarity of a name

Hi, welcome back to Mixed Messages! This week’s guest is author William Rayfet Hunter, who is of mixed-Jamaican and white Irish heritage. The author of Sunstruck, undoubtedly the book of the summer, Will won the #Merky Books New Writers’ Prize in 2022 with this exploration of race, status and the parts of ourselves we risk losing when we fall in love. Think Saltburn, but better – and no bathtub scenes. You won’t be able to stop thinking about these characters – get to know Will’s story here now.

How do you define your identity?

I’m half-Jamaican on my dad’s side. He came here in the ‘60s, his parents a few years before that, the tail end of the Windrush generation. My mum is from an Irish Catholic family, but getting back to Ireland takes two generations above my mum. I have a weird detachment from both lineages - my Jamaican heritage probably goes back to West Africa. Finding an identity through that is part of the challenge.

I describe myself as mixed. During the Black Lives Matter movement, I started more solidly defining myself as a Black person. The world has always viewed me as a Black person and I had resisted that, clinging to my mixed identity. As I get older, I see that as a less helpful distinction. There’s obviously times when I want to be very aware of my position as a light-skinned mixed person, but I identify more as Black as a political identity.

It sounds like your identity has been a journey.

Like most people of colour in the UK, I grew up in predominantly white spaces. My prevailing experience of my own race is how it is read to me by other people, mainly by white people. That always sets up a slight level of discomfort. The people telling me about myself are often not anything like me.

It wasn’t until I was a teenager and moved schools that my race became very apparent to me. For the first time, it was something that could be viewed as a negative or as a tool to undermine me, to read me before I’d opened my mouth.

My grandad on my dad’s side is really light-skinned, lighter than me. My aunty too. Sometimes I’m darker-skinned than some people who are ‘fully’ Black. When I walk down the street and I’m read by a stranger, what category do I fall into in their head? Am I a friendly, light-skinned Black man? A suspicious looking mixed-race guy? Ethnically ambiguous? That’s actually the most common, people want to tell me where they think I'm from.

What I’m reminded of constantly is that I am not white. I’m the ‘other’ category on the form. When it comes down to racial politics in the UK, the big distinction isn’t between mixed-Black Caribbean and Black African, the distinction that matters in most people's minds is white and not white. There are intricacies that are important, but the main political dividing line is white and not white, and I firmly place myself in the ‘other’ category.

In Sunstruck, our central protagonist faces a barrage of microaggressions – does the narrative stem from your own experience?

They’re not things that have happened to me, it’s more a thought experiment based on a collection of experiences dating across race and class. I grew up in quite a middle class background, but was exposed at school to people who were from a very wealthy rarefied background. I also had a lot of friends from working class and less well-off backgrounds, so the intricacies of how class played out in friendships and romantic relationships is something I wanted to explore.

While the story didn't happen to me, the granular detail is very much mine. It's weird, growing up racialised and mixed – you internalise a lot of the microaggressions until you open your eyes to them, or someone, something, opens your eyes. So much of it was feeling uncomfortable, not quite knowing why, and if you expressed that, being told that you shouldn’t react. Your difference is reflected and pointed out to you again and again.

There is beauty in it as well, there's some lovely memories of different storybooks, flavours and smells, knowing that that was in some way special. In geography, we had to choose a country to do a presentation on and I obviously chose Jamaica. I brought in hard dough bread, ackee and saltfish. It was mine and I felt really proud of it.

Was learning about your culture a deliberate act?

It was both absorbed and learned. I don't think my parents set out to deliberately raise us in any particular culture, but we learned about things they felt were important for us to know and identify with. I don’t remember having a sit-down conversation about what it meant until I was older.

Later in life, we spoke about why that didn’t happen, because in some ways I felt like I could have been prepared better for the world. That made my parents quite upset. They were a visibly mixed couple in the early ‘80s, it was traumatic for them. Raising mixed kids in the age of New Labour multiculturalism and, maybe they thought it would be alright. I don't begrudge them. Instead, it was feeling comfortable to go to them and say ‘someone said this, what does it mean,’ or ‘this person does something differently, what is that?’ That curiosity and openness with them is something that I really value.

Now I’m trying to explore parts of Black identity I might have missed out on, not because it was deliberate but because I didn't grow up with that many Black friends. By actively and intentionally building those links, I'm lucky to have found some good friends and community, especially the queer community.

Was it important for you for the main character to be mixed, so he had one foot in both the Black and white communities? Or was it simply reflecting your own experiences?

It’s both. On one hand, I felt more comfortable writing that experience because it is one that I grew up in. Secondly, it's important narratively. Even though it's not explicit in the text, his acceptance into that world is contingent on him being light-skinned and pleasant. He’s pleasant and polite because he’s in awe and because he wants to get on. But his mixed identity, and therefore his light-skinnedness and his lack of being threatening, is important. It’s intrinsic to the access he has to certain spaces.

There’s a central tension in the novel between this white monolith of the Blake family in their world and then this constructed Black other, represented by characters like Jazz, Caleb and Jay. They're deliberately monoracial in their characterisation. Our main character finds himself in-between worlds. Part of the message is that whiteness constructs itself as an absence of race. At the end of the day, he is racialised as a Black person, but at the start, when things are nice and polite and kind, he's racialised as a secret third thing.

It took me until preparing for this conversation with you to realise that the central character isn’t named.

It was initially born out of the fact that I just couldn't name him. As I wrote, I was using White Boy as a shorthand for him, then I realised the Blakes referred to him as ‘darling.’ Those were just placeholders in my mind, then I realised it was intrinsic to the story that he is stripped of his identity. He gains his identity through his interactions with other people.

The book is a journey towards him developing a sense of self. Without a name, he doesn't feel that he has something to hold on to. My publishing name is my full name, which includes my late grandfather's name. Rayfet is quite an uncommon name, there's only a few of us. It helps place my identity outside of the one that you might think when you just say William Hunter. I wanted to honour that part of me, and my granddad who's no longer with us, and also make clear that I'm a Black British author.

Have you noticed any stereotypes around mixed people?

There’s a conception that we’re polite and approachable, in a way we’re raised to be because you don’t know when people are going to switch. Those are nice misconceptions for people to have, but I’m an angry Black man. I'm not gonna be polite. It gets me into heated discussions, because people will ask you really racist shit that they wouldn't say to someone that reads as monoracial, expecting to appeal to your politer side. You asked the wrong mixed person.

What’s the best thing about being mixed for you?

How intrinsically it links to my family. For the first fourteen years of my life, I didn't even conceptualise myself as Black or even mixed. I was a person with an amazing family who had all these differences and similarities, this rich cultural knowledge and heritage. I’m me, and my specific experience is my specific experience.

Parts of it allow me to connect with other people, like my Irish housemate or the Jamaican guy that runs a shop near my house. Where do I find similarity and kinship with all of the people around me, rather than being defined by my difference? That's the most beautiful part of it for me.

There are myriad ways it interacts with my queerness too. The main thing coming out gave to me was this other route into thinking as a marginalised person. It made me a more proud and radical Black person and mixed person. It made me a better feminist. It made me a better ally to disabled people and unhoused people because the more points of difference that you have, the more empathy and understanding you’re about to develop.

How would you sum up your mixed experience in one word?

Ginger. It’s Christmas cooking with my mum's family and Jamaican cooking. It’s a bit of spice, heat, tradition and healing.

Get your copy of Sunstruck at Bookshop.org or Amazon.co.uk now. Next week, I’ll be taking a break, but there may be a very exciting announcement – keep Tuesday July 1st free. Subscribe to get Mixed Messages in your inbox on Monday. Shop Mixed Messages tote bags and bookmarks on Etsy now!

Enjoy Mixed Messages? Support me on Ko-Fi! Your donations, which can start from £3, help me pay for the transcription software needed to keep this newsletter weekly, as well as special treats for subscribers. I also earn a small amount of commission (at no extra cost to you) on any purchases made through my Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links, where you can shop books, music and more by mixed creators.

Mixed Messages is a weekly exploration of the mixed-race experience, from me, Isabella Silvers. My mom is Punjabi (by way of East Africa) and my dad is white British, but finding my place between these two cultures hasn’t always been easy. That’s why I started Mixed Messages, where each week I’ll speak to a prominent mixed voice to delve into what it really feels like to be mixed.

I relate to so much of what William is saying! Identifying as Black later in life, the fact that people for some reason feel “safe” to say all kinds of racist shit around you, the light-skinned privilege. But especially this passage, it hit my heart like a hammer:

“It's weird, growing up racialised and mixed – you internalise a lot of the microaggressions until you open your eyes to them, or someone, something, opens your eyes. So much of it was feeling uncomfortable, not quite knowing why, and if you expressed that, being told that you shouldn’t react. Your difference is reflected and pointed out to you again and again.”

Looking forward to reading Sunstruck!

I don't have words for the immediate kinship & understanding I felt in every bit expressed here. It's so wonderful to read about the additional intersectionality and layer of queerness to the mix!

I feel less lonely 🙏🏽 I gotta find this book!